Hannah Arendt beyond Martin

Why so many biographies about Arendt focused on her love affair with Martin Heidegger and what does it mean?

I have this idea, which I rarely shared with others, that the great interest in Arendt’s life (the reason for so many biographies) is informed by the specific interest in her love affair with Martin Heidegger. That’s why many people feel some kind of intimacy and even call her just “Hannah” as if she were a kind of philosophical “Frida”, whose love life is fetishized for the sake of a pseudo-sensibility commonly attached to women. Nobody does such a thing with Judith (Butler), Simone (de Beauvoir), or Angela (Davis), for example. I know, Arendt wasn’t a feminist, let alone an activist, and I can see many flaws due to her lack of interest in women’s problems in her work, especially in “The Human Condition”. But I dare to say she would find it really picturesque that interest in her life puts her work in second place and this huge interest is driven by a love affair she had when she was 18 years old. This distorted view of Heidegger’s role in Arendt’s life and work is the result of a sexist, patriarchal mindset, that determines the love affairs of a woman surpass her work and sparkle interest in a voyeuristic fashion, putting her private life under scrutiny and her public persona under the shadows.

I’ve heard and read many times about how beautiful was the love story between Arendt and Heidegger. Even theatrical plays were made to portray it. But this assumption of the power of Heidegger over Arendt is often misread and the love story is in many ways distorted to fit into romantic and sometimes kitschy imagery. Arendt found love on other occasions, with other men, and made a career as one of the most important thinkers of the century in her own right, but she still being remembered for and defined by the affair she had with her professor when she was between 18 and 22 years old. As for Heidegger, Hannah Arendt is worth some pages, maybe just some paragraphs in his biography.

Immediately after her doctorate on love and Saint Augustine, Arendt was interested in the life and legacy of Rahel Varnhagen and researching questions related to German Jews. She and her then-husband Günther Stern collaborated closely with each other’s ambitions while together. Under the shadows of the war and its consequences, both understood that if philosophy would still have any meaning, it should deal with urgent and persistent problems of the present and the immediate past. They were very different and their marriage was for a short time, but they remained in conversation during their lives and worked on the same issues from different perspectives. More about their story together can be found in their correspondence and in this book he wrote after her death.

Then Arendt met Heinrich Blücher and with him, the relationship was not only a love story but an “eheliche Gedankenwerkstatt” (a couple-thinking workshop) very little discussed and very underrated in the accounts about Arendt’s life and work.

In “Origins of Totalitarianism” her husband and partner through life, Heinrich Blücher, was the primary interlocutor during the writing process. In “The Human Condition” the influence of her dialogue with Blücher is very clear, especially in her interest and reflections on mass society and on Marx. Blücher lacked an academic background but had abundant practical knowledge gained not only through readings but from his experience as Spartacist and his many other political engagements. A Genie des mündlichen Denkens, as Kurt Blumenfeld would refer to him, Blücher was not only the great love of Hannah Arendt but had also a major influence on her thought and the way she saw the problems of her time. With Blücher, she once said, she learned how to think politically.

From Heidegger, she learned a new way to do philosophy, and adopted his passionate poetic thinking (dichterisch denken) and views about the collapse of Metaphysics. Another mentor of hers was Karl Jaspers, with whom she developed a correspondence of major importance to anyone who wishes to study Arendt’s legacy. Jaspers was her thesis supervisor who turned into one of her great friends and with whom she discussed key aspects of many of her works. This relationship too was overshadowed and is not explored as it should be, with rare exceptions. Maybe partly because we can’t gossip about it, but maybe also because in this particular relationship, she is not playing the role we usually like to see women in: as a lover, living for and guided by her feelings.

I’m not saying Heidegger didn’t influence Arendt. He did, he was her mentor, as for many other of his male students, who also were deeply influenced by him. Renowned thinkers like Gadamer, Marcuse and even the disappointed Hans Jonas were fascinated by his ideas. But as for Arendt, the main interest is guided by the voyeuristic curiosity over a love affair, affecting her academic reception, but not his. In the so many biographies written about Arendt, the vast majority explore this love affair and put it as a central aspect of her life and thinking. Hence so many biographies tell us more of the same.

We have stellar biographical works like Elisabeth Young-Brühel’s “For the love of the world”, published in 1982 with Yale University Press. In analyzing the female genius, Julia Kristeva’s “Hannah Arendt” (Fayard, 2001) provides a powerful and beautiful narrative of Arendt’s work and life and is one of my favorites. Kurt Sontheimer “Hannah Arendt: Der Weg einer großen Denkerin” (Piper Verlag, 2005) explores Arendt’s life focusing on the aspects informing her work, putting her at the center of the narrative. Recently, Arendt scholar and writer Samantha Rose Hill published “Hannah Arendt” (Reaktion Books, 2021), presenting new aspects of Arendt’s life in a fascinating and vibrant narrative. Hill’s text, as for Brühel, Kristeva and Sontheimer, presents ways and facts that help us to interpret Arendt’s ideas, giving us the possibility of active reading: instead of passively reading a story, we are invited to think about what this story means in the context of the philosophical legacy of Arendt.

This year a new biography will be published: Thomas Meyer’s “Hannah Arendt” (Piper Verlag). According to the presentation text, new sources and a specific leitfaden will guide the way through Arendt’s life. Many biographies were written, but we can’t get enough of the companionship of those who invite us to think together. As for the works about “Hannah and Martin”, we have also some interesting and rich accounts, that surpass mere romanticization and give us not only a narrative about a love affair but also keys to comprehension of the mutual influence in each other lives and reflections. I’ll present some of my favorites.

The first one is Dana Villa’s “Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political” (Princeton University Press, 1996). in this book, Villa offers us a new way to interpret Arendt and the influence of Heidegger in her theory of action, showing how she followed both Heidegger's and Nietzsche's critiques of metaphysics but managed to draw a radically different response to political problems of her time, explaining how her project relates to the “death of God”.

Another great account of the liaison between Arendt and Heidegger is Tatjana Noemi Tömmel’s book “Wille und Passion: Der Liebesbegriff bei Heidegger und Arendt” (Suhrkamp, 2013). In this book, the author discusses the fact that the love affair of Arendt and Heidegger is on everyone’s lips, but their philosophical reflections on the concept of love are almost unknown. Exploring this “terra incognita” from a large number of fragments, Tömmel reconstructs the systematic function that the concept of love has in the work of both authors, also tracing the silent dialogue that Arendt had with Heidegger about love.

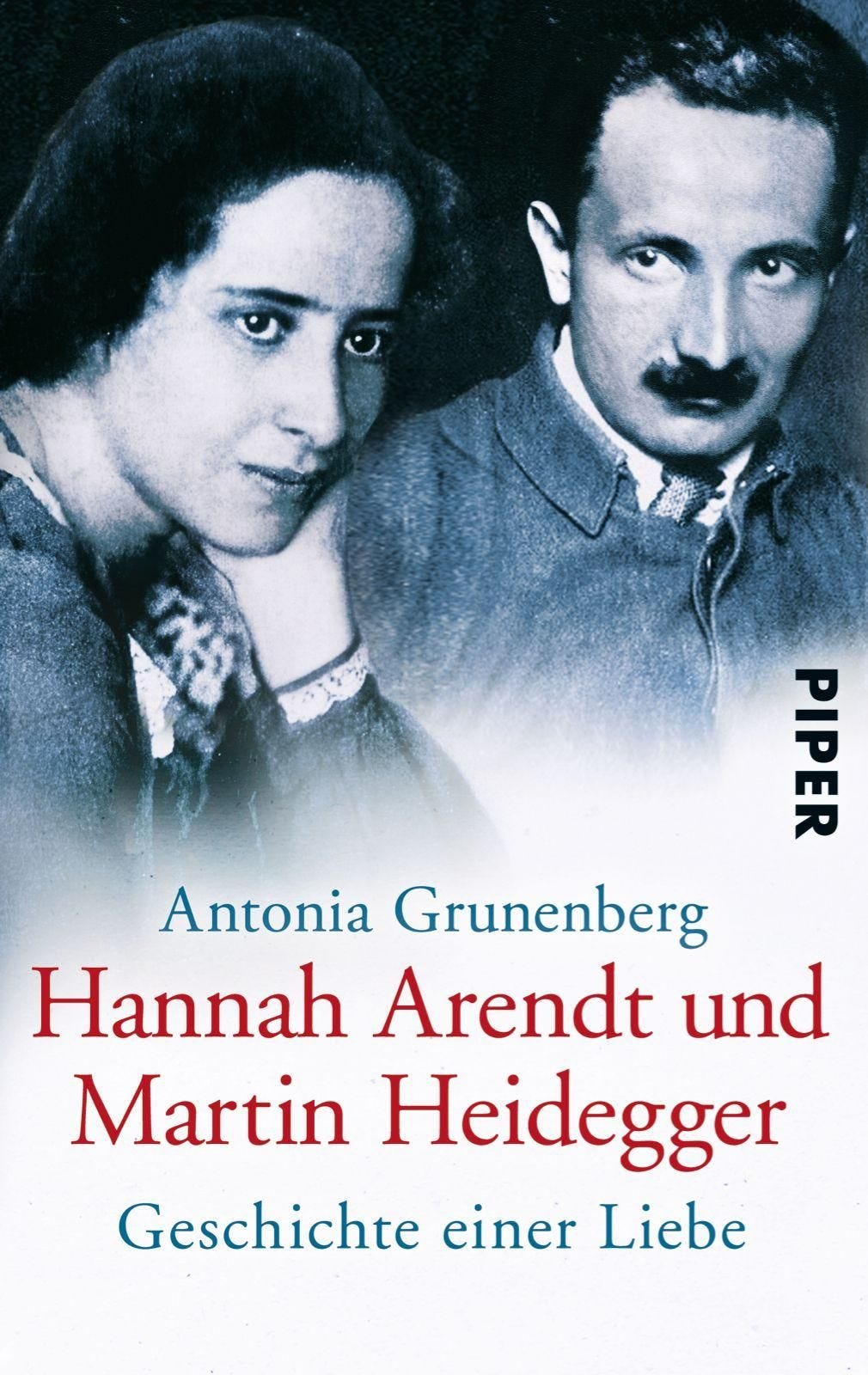

For those interested in a narrative about the love liaison Arendt/Heidegger I recommend Antonia Grunenberg's book “Hannah Arendt und Martin Heidegger: Geschichte einer Liebe” (Piper Verlag, 2006). It was translated into many languages: English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese editions are easy to be found online. The way Grunenberg approaches the love story is creative, then she tells this story in a way that the personalities and ideas of both thinkers are used as background for the development of the narrative: the paths of love and the paths of thinking, Eros und Denken.

Many other works could be listed here, but my choice was to select just a few exemplary books and emphasize how Arendt’s life is way more interesting than one love affair she had. And that reducing this relationship to a romantic liaison, ignoring its complexities, not only drives us to misunderstandings but also to a pattern of reducing women to romantic archetypes, even when they are great thinkers in their own right, like Hannah Arendt. Her friendships, her experiences and yes, her lovers, are part of her life and play an essential role in her thinking since they influence and inform her views. But isn’t so with all of us?

L*